The UN has expressed concern over a radical EU-Turkey plan to ease the migrant crisis, saying it could contravene international law.

Under the plan, all migrants arriving in Greece from Turkey would be returned and for each Syrian sent back, a Syrian in Turkey would be resettled in the EU.

The UN’s refugee agency said any collective expulsion of foreigners was “not consistent with European law”.

Amnesty International called the plan a death blow to the right to seek asylum.

The deal, discussed at a summit in Brussels on Monday, has not been finalised and talks will continue ahead of an EU meeting on 17-18 March.

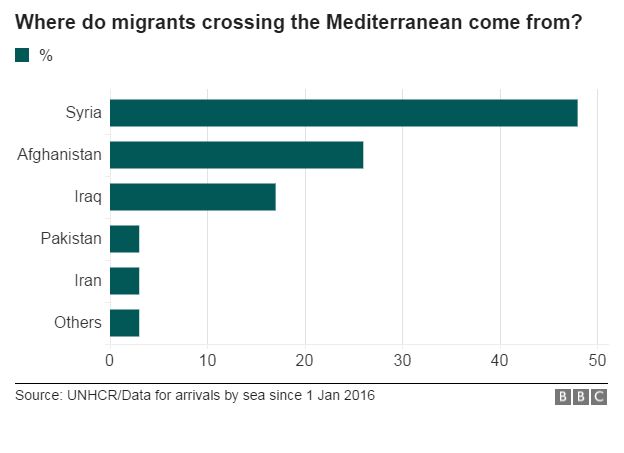

Europe is facing its biggest refugee crisis since World War Two. Last year, more than a million people entered the EU illegally by boat, mainly going from Turkey to Greece.

Most of them were Syrian, fleeing the country’s four-year civil war. Another 2.7 million Syrian refugees are currently in Turkey.

What’s in the EU-Turkey proposal?

The EU heads said “bold moves” were needed to tackle the crisis, and made the following proposals:

- All new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey to the Greek islands will be returned to Turkey, with the EU meeting the costs. Irregular migrants means all those outside normal transit procedures, ie without documentation. The term “illegal migration” usually refers to people smuggling

- In exchange for every returned Syrian, one Syrian from Turkey will be resettled in the EU

- Plans to ease access to the EU for Turkish citizens will be speeded up, with a view to allowing visa-free travel by June 2016

- EU payment of €3bn ($3.3bn; £2.2bn) promised in October will be speeded up, and a decision will be made on additional funding to help Turkey deal with the crisis. Turkey reportedly asked for EU aid to be increased to €6bn

- Preparations will be made for a decision on the opening of new chapters in talks on EU membership for Turkey

How have leaders reacted?

European Council President Donald Tusk insisted the leaders at the summit had made a “breakthrough”, and he was hopeful of concluding the deal in the next week.

He said the progress sent “a very clear message that the days of irregular migration to Europe are over”.

Read more about the migrant crisis

- Crisis explained in seven charts

- How different countries have been affected

- Key migrant crisis questions answered

- Have previous EU migrant deals delivered?

- Disquiet over deal with Turkey

However, German Chancellor Angela Merkel was more circumspect, saying: “It is a breakthrough if it becomes reality.”

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said Turkey had taken a “game-changing” decision “to discourage illegal migration, to prevent human smugglers, to help people who want to come to Europe through encouraging legal migration”.

The BBC’s Selin Girit says that although Turkey feels it has played its cards well, this plan will need full EU-Turkey co-operation to work. She says Turkish media have hailed the plan – particularly the visa-free access – but critics have accused the EU of turning a blind eye to Turkey’s human rights record.

What are the legal concerns?

Vincent Cochetel, the UN’s regional co-ordinator for the refugee crisis in Europe, said: “An agreement that would be tantamount to a blanket return of any foreigners to a third country is not consistent with European law.”

Amnesty International said the plan was “wrought with moral and legal flaws”.

Iverna McGowan, head of Amnesty’s International’s European Institutions Office, said: “EU and Turkish leaders have sunk to a new low, effectively horse trading away the rights and dignity of some of the world’s most vulnerable people.”

The EU believes the legal questions will be covered by declaring Turkey a “safe third country” for return. Only one member of the EU – Bulgaria – has done this so far. Amnesty says it strongly questions the whole concept of “safe third country”.

Turkey is also not a full member of the Geneva Convention, which could raise more legal questions.

Can the return system work?

The system spelled out to the BBC by EU Commission spokesperson for migration Natasha Bertaud would see all migrants rescued in Greek waters taken to a Greek island for screening.

Irregular migrants would then be returned to Turkey where they would be screened again and “if they have no right to international protection” (which currently covers only Syrians) sent back to their country of origin.

All migrants rescued in Turkish waters would be taken back to Turkey, which would decide their status.

Serious questions remain.

What will happen to the thousands of migrants already in Greece, which has struggled to shelter and register them?

What will happen to the thousands of migrants already in Greece?

The one-in, one out system also only applies to Syrians. What will happen to all the other migrants returned to Turkey? Again the legality of their return must be considered, as must Turkey’s capability to return them to their countries of origin.

The biggest problem, though, will be the migrants themselves – having risked their lives and invested much of their money, will they not simply try other routes? The migrants in the Calais camp known as “the Jungle” have not been known to give up on their attempts to reach the UK.

Vincent Cochetel said the migrant route would merely fragment: “As long as the conflict is not solved, it’s a myth to believe that people will not try to leave.”

As for resettlement, there is major opposition among some EU members to compulsory migrant quotas.

What are the other obstacles?

Hungary, which has taken a strong anti-migration stance, says it vetoed the Turkish resettlement proposal on Monday and may do so again at the next EU meeting.

Turkey’s bid for EU membership. A long and thorny issue, not helped by the recent press-freedom wrangle over the court-ordered seizure of the opposition Zaman newspaper. Given all the hurdles, though, this is not a pressing concern.

More problematic is Turkey’s request for visa-free access for all its citizens to the EU’s Schengen zone, which it hopes to achieve by June. This may draw a lot of opposition.

The future of Schengen – which allows passport-free travel in a 26-nation zone – is already in doubt, given that eight of its members have introduced temporary border controls.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

BBC

Q FM Africa's Modern Radio

Q FM Africa's Modern Radio