Blood doping: Is fixing athletics Lord Coe’s greatest challenge?

Two weeks before its flagship event – the World Championships in Beijing – and with its credibility and integrity under scrutiny like never before, it is no surprise that athletics’ governing body the IAAF has come out all guns blazing as it attempts to handle the drugs crisis that threatens to bring the sport to its knees. But what questions remain to be answered?

There is little doubt it feels athletics is getting a raw deal as a result of the publication of allegations by German broadcaster ARD and the Sunday Times that it effectively turned a blind eye to rampant cheating and suspicious blood tests involving hundreds of athletes – allegations the IAAF calls “sensationalist and confusing”.

In a lengthy and robust statement, the IAAF made some valid points; the majority of the blood readings were taken before the introduction of the ‘biological passport’ in 2009, cannot be used as proof of doping, and are not the same as failed tests. What they are is essentially an indicator, a clue, open to interpretation, and potentially explained by a range of factors – from altitude to pregnancy and illness. The database was indeed shared with world anti-doping agency Wada, so why, they ask, did its chief, Sir Craig Reedie, express his surprise at the allegations?

Despite the profile afforded to it by being the biggest of the Olympic sports, athletics is a minnow in financial global sporting terms. With revenue of just £40m a year, there is clearly a limit to what the IAAF can do to police its sport with only 10 people employed to oversee testing. It has indeed pursued 63 cases based on the biological passport programme with 39 athletes punished. It had targeted, tested and caught dopers. Athletics conducts a lot more tests than many sports, and it is clearly unfair to suggest it has sat there and done nothing.

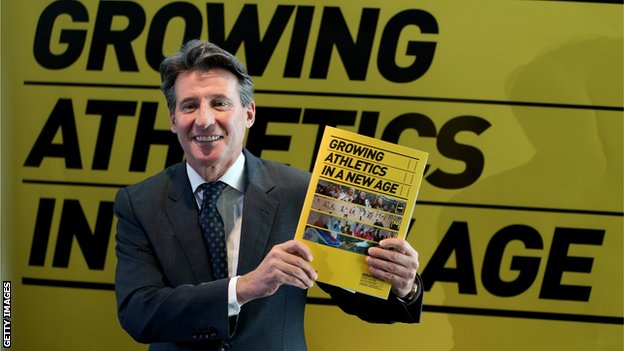

IAAF vice-president Lord Coe was even firmer in his defence of the sport, describing the allegations as a “declaration of war” against track and field and citing the interpretation of the data as “breathtaking ignorance or a level of malevolence”. Naturally perhaps, for a man who loves the sport he once graced, Coe did not hold back, calling the coverage “selective” and “wrong”, and an attempt to “destroy the reputation of our sport”.

With the credibility of athletics on the line, the anger of Coe and the IAAF at the damage being done is understandable, and they are fully entitled to their opinion if they feel hard done by.

But as athletics braces itself for more revelations this weekend, its stance has undoubtedly disappointed some critics who want the sport to acknowledge, rather than deny, that it has a major problem. After all, outgoing IAAF president Lamine Diack admitted to me earlier this year his sport was indeed “in crisis”.

Some athletes have come out and said the revelations merely confirmed their suspicions, and would rather the IAAF use the scandal as a catalyst for change than vent ire at the impression it has created. Sergey Bubka, Coe’s rival in the presidential election taking place on 19 August, took a very different approach in his response to the crisis, calling for more transparency and admitting the IAAF needed to be “more proactive”.

This week Diack described the allegations as “a joke”. Very few are laughing. As Dick Pound, former head of Wada, said: “I’m not sure what he meant.”

Pound is currently heading a Wada independent commission investigating earlier allegations of widespread doping and cover-ups in Russia. in 2013 he told the Mail on Sunday: “It’s clear that cycling, athletics, swimming, tennis and soccer have major problems and are ruled by governing bodies in denial.”

Dick Pound, the former president of Wada, was listed as one of the “100 most influential people in the world” in 2005 by Time Magazine

A central plank of Coe’s IAAF presidential election campaign has been getting tougher on doping and he has spoken about life bans for those caught cheating. However, given his involvement in the IAAF for several years, and his condemnation of the media outlets who have exposed the leaked files, is he too close to make those changes?

By threatening legal action against the whistleblower and attacking the messenger, athletics leaves itself open to comparisons with the way Fifa attacked the BBC and the Sunday Times over its exposes of corruption surrounding World Cup bidding in recent years. Many will argue the story is of significant public interest, and that the IAAF and Coe were too quick to dismiss it after just a few days.

The IAAF can hardly be surprised some are sceptical. After all, back in December it was forced to deny those previous allegations of institutional doping at the Russian athletics federation. The son of the president himself, Papa Massata Diack, an IAAF marketing consultant, stepped down pending an investigation, along with Valentin Balakhnichev, president of the Russian athletics federation and the IAAF’s treasurer. Months later, we are still waiting for both the IAAF’s internal ethics committee investigation – and Wada’s Independent Commission investigation to report back.

Coe’s questioning of the credentials of the “so-called experts” who interpreted the readings from the leaked database – anti-doping scientists Robin Parisotto and Michael Ashenden – has also raised eyebrows. Parisotto, after all, is employed by the Russian Anti-Doping Agency. Ashenden is regarded as one of the world’s foremost experts on blood doping. He has acted as an expert witness in high-profile cases including those of cyclists Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador.

It will not have escaped attention that as recently as 2012, the IAAF rated Ashenden highly enough to ask him to sit on an expert panel on biological passports, but he declined because he felt he was being “muzzled”, accusing the anti-doping movement of fostering a culture of ‘omerta’. So it is inevitable, fair or not, that some will now see echoes of the way cycling was run during the EPO era, when those in charge of the sport averted their eyes instead of tackling the problem head on.

The two experts have made the point that when the IAAF analysed the same data that has been reported, it felt sure enough to report that increased blood values “most probably indicated a doping behaviour”, and there will now be calls for the entire database to be passed over to Wada’s Independent Commission.

Some will want to know whether Coe now supports the idea of criminalising doping, as some countries have done. And whether athletes should now publish their blood results, if they have nothing to hide. Does he support the idea of banning entire countries from competition – like Russia (despite the power it wields in world athletics) – if their athletes continue to cheat.

Some will ask why Coe asked for ARD and the Sunday Times to hand over the data – “we would love to know what they have got” – when the IAAF readily admits it already has it. Coe also quite rightly referred to the dangers of extrapolating from “one set of readings”. But Ashenden and Parisotto have said, their judgements were based on a number of samples, – “the entire blood profile”.

What is blood doping? |

|---|

| Sports nutritionist Eleanor Jones says blood doping can help endurance athletes by increasing their ability to transport oxygen around the body. |

| She told BBC Radio 5 live: “It works like giving blood, except that after you’ve replaced that donation naturally in your body, you then reinfuse the blood that you removed originally, so you might have 110% of your normal blood volume.” |

These are challenging and awkward times for Coe. Last month he came out and publicly supported Mo Farah’s decision to back his coach Alberto Salazar after the American’s denial of any wrongdoing following allegations in a BBC Panorama documentary that he had violated doping regulations. There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing by Farah, but some would no doubt have preferred Coe to wait until the outcome of investigations by US Anti-doping Agency into the claims, and for UK Athletics to publish their full report into the training regime of the coach (who they use as a consultant) at Nike’s Oregon Project.

Last week, before news of the doping scandal broke, my colleague Alex Capstick interviewed Coe and asked him if his judgement was compromised by being an international adviser to Nike. Coe denied it, and said he was proud of his record on transparency and corporate governance, but did say it was “possible” he would have to now reconsider the long-standing relationship. For all of the support they have given to track and field, Nike, remember, have been criticised by a number of athletes for their sponsorship of two-time drugs cheat Justin Gatlin.

Talking of which, later this month, Gatlin is favourite to win gold in the 100 metres final in Beijing. Given everything that has happened, some will see it as the last thing athletics needs. Having just seen Chris Froome win the Tour de France under a cloud of innuendo without any evidence, athletics cannot afford for every medallist in Beijing to do so with millions of viewers wondering if they can believe what they see.

Coe is clearly in a tricky position, and obviously he will only have the opportunity to make the required changes to athletics if he wins the forthcoming IAAF presidential election against pole vault legend Bubka. For many, Coe is the man to clean up athletics; he has called a for a properly-resourced independent testing programme, and if he wins, must be judged on what he does in office.

But rarely will a new international federation president have come into power at such a pivotal time for their sport. Coe may have thought winning Olympic races or organising the London 2012 Games was difficult. Fixing his sport – if given the chance – could prove his toughest challenge to date.

BBC Sport

Q FM Africa's Modern Radio

Q FM Africa's Modern Radio